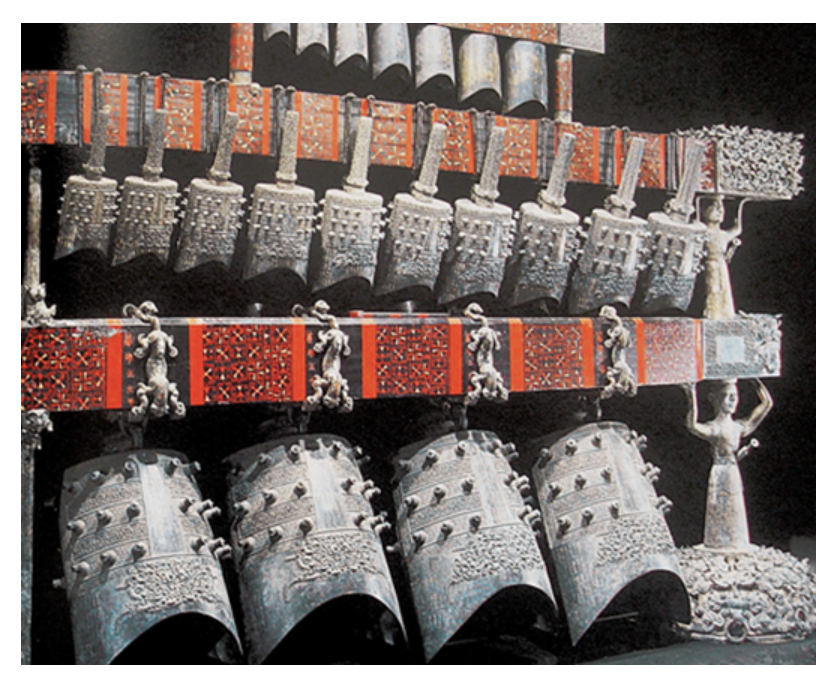

With so much “misinformation” about pitch, scales, and tunings resonating throughout internet land, whenever reliable sources on music history come my way, I investigate. I had a conversation with Joscelyn Godwin, a musicologist, about a recently discovered ancient instrument. He told me that in 1978, a set of Chinese bells, that are 2,500 years old, were found in a tomb! You might ask, “what’s a musicologist?” They are musicians with an advanced degree in music (PhD) who often work in large museums or universities. Anyone else who reports on music history that doesn’t have an advanced music degree is a “music enthusiast,” not a musicologist.

That groundwork now laid, enter (from stage left) the Marquis Yi of Zeng’s Bells…. They were found in a tomb in China dated to 433 B.C. This date is close to the time of Pythagoras where he’s said to have “discovered” our modern musical scale. The Pythagorean tuning system is built on simple ratios and follows the musical harmonic series. The biggest question to ask is who “discovered” and used this form of tuning first? Was it the Chinese or another culture? Pythagoras’ scale was used by Guido d’Arezzo (around 1,000 AD) when he taught monks how to read music using his new “solfeggio scale.” Now that we have a set of tuned bells from the time of Pythagoras, we know what Guido d’Arezzo’s scale sounded like 1,500 years later!

The so called "ancient solfeggio frequencies" first reported by Joseph Puleo and Leonard Horowitz don't fit within the same scale system. Therefore, I can say that the frequencies Puleo and Horowitz propose as the “ancient solfeggio frequencies” that were supposedly lost are NOT the “true” solfeggio frequencies. Why? Because they don’t match the intervallic structure used for tuning the Zeng bells or for Guido d’Arezzo’s method of teaching the plainchant repertoire. Because Guido d'Arezzo put plainchant into sheet music, anyone who reads music can sing the repertoire as it was originally intended.

Moving along to the bells of Zeng...

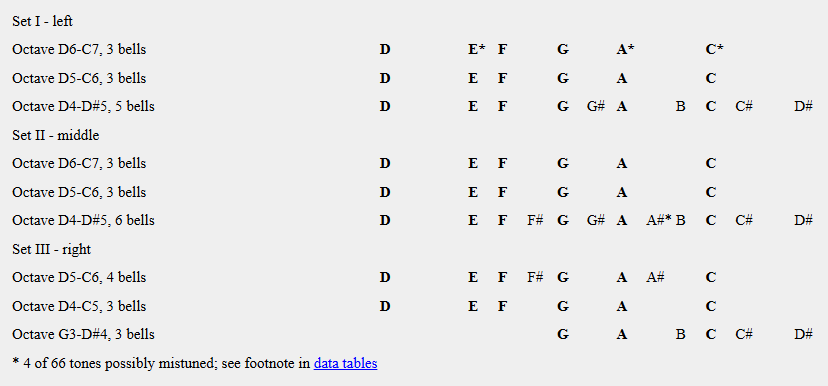

Musicologist Martin Braun provides the basic information about the Zeng bells. He states that “A unitary ensemble of 65 bells, with 130 discrete strike tones, was excavated in a fully preserved state 1978 in the Chinese province of Hubei from the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng from 433 B.C. The ensemble's tuning system could now for the first time be determined by applying exclusively empirical methods. The results show tuning with equally tempered fifths (~696 Cent) in the series CGDAE.”

Zeng Bell Details

- They are tuned in both thirds and fifths. However, the tuning focus was on pure thirds, not pure fifths.

- The bells are based on a 12-tone system but, not like the white and black keys on a piano. This is explained further in my correspoding video (posted below).

- 33 melody bells in the middle tier repeat a six-tone scale eight times. Those notes are D-E-F-G-A-C.

- In five of the eight sets of bells (from the melody section), the six-note scale (Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Do) is a subsection of three adjacent bells.

- In the three subsections, each of the five three-bell groups start with six single tones (D-E-F-G-A-C). The three extra bells have two tones per bell: first bell D-F, second bell E-G, and third bell A-C.

- The order of octave repetition indicates a subdivision of the three bell rows of the middle tier into 9 groups of 3-5 bells each (see Figure 1).

- The D-E-F-G-A-C scale (Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Do) uses the same tones as the six note scale (Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, So, La) that was first highlighted by Guido d’Arezzo from the early 11th century A.D. NOTE: Guido’s scale was used to teach the monks “sight singing” so they could learn the plainchant repertoire from sheet music rather than by rote.

- The Zeng bells have 6 main tones (Re, Mi, Fa, So, La, Do) and 6 accidentals (sharps/flats). As shown in Figure 1, there is only one complete chromatic 12-tone scale. Three further octaves have four, three, and two accidentals. This is discussed further in the corresponding video below.

- Based on pitch data from the bells, the “norm tone” (tuning note?) is an F (1st space of the treble clef) and was 20 cents lower than modern A=440 concert pitch. This would put the tuning of the entire bell set at around A=426.6 Hz.

- The bells are playable in Pythagorean tuning, Just Intonation, and equal temperament, according to a variety of musicologists. I speculate as to why this is in the corresponding video.

In my conversation with musicologist Joscelyn Godwin about the Zeng bells, he replied in an email after the conversion (October of 2024) that the...

Figure 1

“Chinese were probably integrating their tonal system with the diurnal cycle. We know this from tonal analysis of the "Carillon of the Marquis of Zeng," excavated in 1978 and now preserved in a Wuhan museum. The 60 bells are accurately enough tuned to incorporate both Pythagorean and Just intonation.”

Godwin also said that the lowest bell is about 64 Hz (the lowest note on a cello). In his email, he added, “The Chinese used the Babylonian units of hours, minutes, and presumably seconds. If indeed they tuned C to an "octave" of 1 Hz, they were deliberately attuning their tonal system to their time system as a harmonic division of the length of the day. This could have been done with a water-clock and using the phenomenon of beats.”

Figure 2

A water clock is the precursor to time-keeping devices that scholars say was probably invented by the ancient Sumerians sometime in the 14th century B.C.E. The other name for the device is “clepsydra.” The water clock was a bowl-like canister made of stone. It had a hole in the bottom that controlled the flow of non-stop water. The holes directed the water flow to other similar containers that the water overflow ran into. Time could be measured based on water levels within the cannister. (Figure 2)

History of Trade in China with Ancient Greeks

Pythagoras died in 495 BC. The Zeng bells were made around 433 BC (62 years apart). It is known that China traded silk with Greece during this time. There’s always curiosity between humans when they find something new and different. Could the two countries have shared ideas as well as goods? Without doing a full deep dive into the history of these two countries, we can assume trade went beyond silk. What ideas did they share? Did Pythagoras gain information from the Chinese or was it the other way around? Based on the making of ancient gongs, it appears the Chinese used cymatics for tuning their gongs. Their version of a water clock dates to the 6th century, which is during the time of Pythagoras and the Zeng bells. Therefore, this is another reason I suspect that the ancient Greeks and Chinese traded more than silk.

Pythagorean tuning is based on the tuning of fifths followed by octaves. Eventually, all notes within the scale are tuned by using downward and upward Perfect fifths until every note within a couple of octaves has been tuned. Once each note is accounted for, higher and lower notes are tuned by the octave. This method of tuning is evident as early as ancient Sumeria (found on a cuneiform tablet) and is still in use today by piano tuners with variations for equal temperament. However, as mentioned above, the Zeng bells of China were tuned according to Major 3rds, which is one reason there are slight differences.

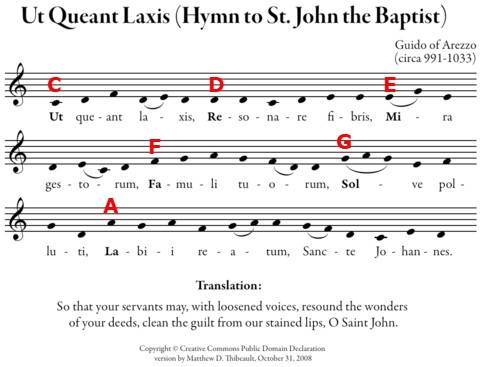

Guido d’Arezzo’s scale started with Ut (C) Re (D), Mi (E), Fa (F), So (G), La (A). In the Keng bells, the starting pitch is D (Re) and ends with the C (Do/Ut). Guido used this scale in his Hymn to St. John the Baptist. See Figure 3 where I put the actual note names above the solfeggio symbols.

Figure 3

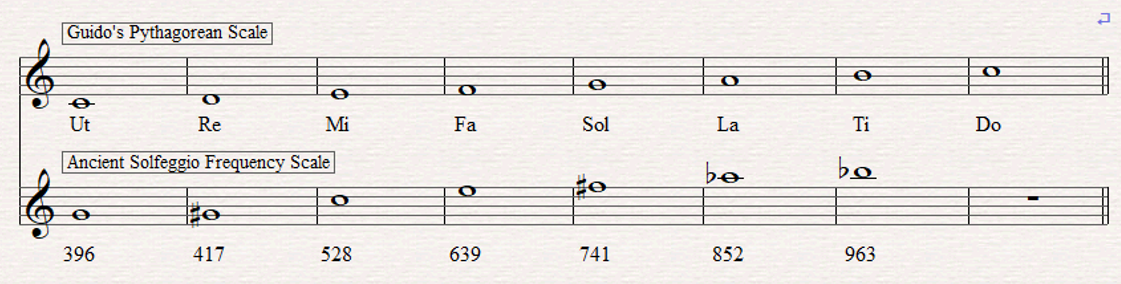

In comparison to the scale found in the tuning of the Zeng bells and the Hymn of St. John the Baptist, let’s look at pitches for the ancient solfeggio frequencies introduced by Puleo and Horowitz and compare them to Guido’s scale and the Zeng bells. You'll notice that Puleo's frequencies are not even close to the others and don't even create a scale. Scales are combinations of Major 2nd's, minor 2nd's, and some include minor 3rd's. Look at the distance between each note. Scales are determined by the pattern of intervals from note to note. See Figure 4 for the musical pitches of Guido's scale compared to Puleo's frequencies.

Guido's scale intervals (distance between notes) C-D = Major 2nd, D-E = Major 2nd, E-F = minor 2nd, F-G = Major 2nd, G-A = Major 2nd, and A-C = minor 3rd. It's a combination of dorian mode (in D) and the pentatonic scale, even though the tune begins on C.

Puleo's and Horowitz's frequencies create the following intervals G-G#/Ab (396 - 417 Hz) = minor 2nd, G#/Ab - C (417 - 528 Hz) = Major 3rd, C-E = Major 3rd (528 - 639 Hz), E-F# = Major 2nd (639 - 741 Hz), F#-G#/Ab = Major 2nd (741 - 852 Hz), and G#/Ab - A#/Bb = Major 2nd (852 - 963 Hz).

Zeng Bells scale intervals D-E = Major 2nd, E-F = minor 2nd, F-G = Major 2nd, G-A = Major 2nd, A-C = minor 3rd.

NOTE: Modern music theory assigns TWO names to the black keys (sharps and flats). They are two different note names but are the same sound. We call them "enharmonics." Enharmonics were created when equal temperament became the standard.

Figure 4

I find it interesting that the main notes of the Zeng bells are the same notes used by Guido d’Arezzo to teach monks sight singing. Ut (now Do) is generally assigned to the first note of any scale (in movable Do). However, it wasn’t until the invention of the keyboard that the sharps and flats were explored to a greater extent. Now that we have historical evidence showing the tunings of the Zeng bells, we know the scale Guido used was used at least 1,500 years before his time.

Early keyboards (prior to equal temperament) tuned the sharp notes lower than flat notes. Sharps and flats were originally two different notes (but still quite close). This information is a bit musically geeky for this article. If you want more information, look for videos on tuning of early keyboards (Baroque era).

Conclusion

As ancient musical instruments are unearthed in archaeological digs, we learn more about the history of music. Because the musical harmonic series is found in nature, our "being" naturally wants to resonate with it. Therefore, the harmonic series is a part of who we are whether we know it or not. Click on the link (above) to watch a short video on the musical harmonic series. I also discuss more about the harmonic series in the corresponding video because it completely explains how scales were originally "discovered."

It makes sense that ancient civilizations intuitively understood the harmonic series and used it even if they didn't understand the techniques of it. When you take a string and pluck it, it creates a tone. Dividing it in half creates an octave and so on. We did experiments creating harmonics in my junior high science class but did we really understand what we were doing? We just thought it was cool.

If we played with the harmonic series in school, why do we think the ancients wouldn't have dome something similar? We assume modern technology is far more advanced than previous civilizations but we're finding out otherwise. After all, no scientist really knows how the Great Pyramid was built so obviously there's a lost technology that we have yet to understand. Why do we think the ancients couldn't figure out the harmonic series, especially since it's part of nature?

When comparing Marquis Yi of Zeng's bells from 433 BC with Guido d'Arezzo's musical scale of 1,000 AD, they are nearly identical scales but with minor differences in temperament. Temperament involves adjusting the distance BETWEEN notes. As mentioned at the beginning, as long as a musician performs in the A=426.6 Hz concert pitch, he/she can use the temperaments of Just Intonation, Pythagorean tuning, or equal temperament to play along with the bells. That indicates there's only slight differences between the three tuning systems. In looking at Puleo's frequencies, there's absolutely no way they fit within the musical harmonic series pattern.

Although I've already provided a lot of information about the ancient solfeggio frequencies, we now have real evidence of ancient instruments showing us HOW the ancients tuned instruments. Because we can determine the exact frequencies (in Hz) of the Zeng bells, we can fully understand their tuning. 1,500 years later, Guido d'Arezzo put the plainchant into sheet music and when comparing the bells of 433 BC to 1,000 AD, the tuning is a close match. Therefore, there's no such thing as the "ancient solfeggio frequencies" nor were they lost in time as Horowitz or Puleo state. The "solfeggio" scale was first introduced by Guido d'Arezzo. With slight differences in equal temperament vs Pythagorean, the Hymn to St. John the Baptist sounds very much the same today as it did in Guido's time. The main difference is that the scales of today added a 7th note (Ti) to music in the renaissance era. And, the distance between notes differs slightly from equal temperament. Yes, Pythagorean tuning and Just Intonation might sound a little odd to the modern ear but... melodies are still recognizable. That would not be the case if Puleo's frequencies were used in place of the scale used by Pythagoras, Guido d'Arezzo, and the bells found in the Zeng region of China.

As I've said before, intention plays a HUGE role in healing music. If you enjoy Puleo's frequencies and find them helpful, use them! It's all in the eye of the beholder (or listener).

Corresponding Video

Sources & Links

The article by Martin Braun provides key details of the bell tunings. The chart in Figure 1 came from Braun's site. The YouTube videos provide additional details along with demonstrations.